INSIDE: approximately 6 hours

BACKSIDE: approximately 81 minutes (presented on a continuous loop)

(Both videos run concurrently)

By Alfonse Chiu and Elysa Wendi

The initial encounter with a powerful work of art is always special. In the writing of this essay, the authors have revisited the memories of where they first caught INSIDE. For artist-curator Elysa Wendi, initially, she drifted in and out like in a dream, which intrigued her to a second visit where she stayed for the entire duration of six hours. For writer and curator Alfonse Chiu, the encounter began as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, where the work served as a transfixing portal into an interior world both distant and familiar. In both cases, encountering INSIDE necessitates a kind of fugue state that follows the ebb and flow of light and body towards the sublime.

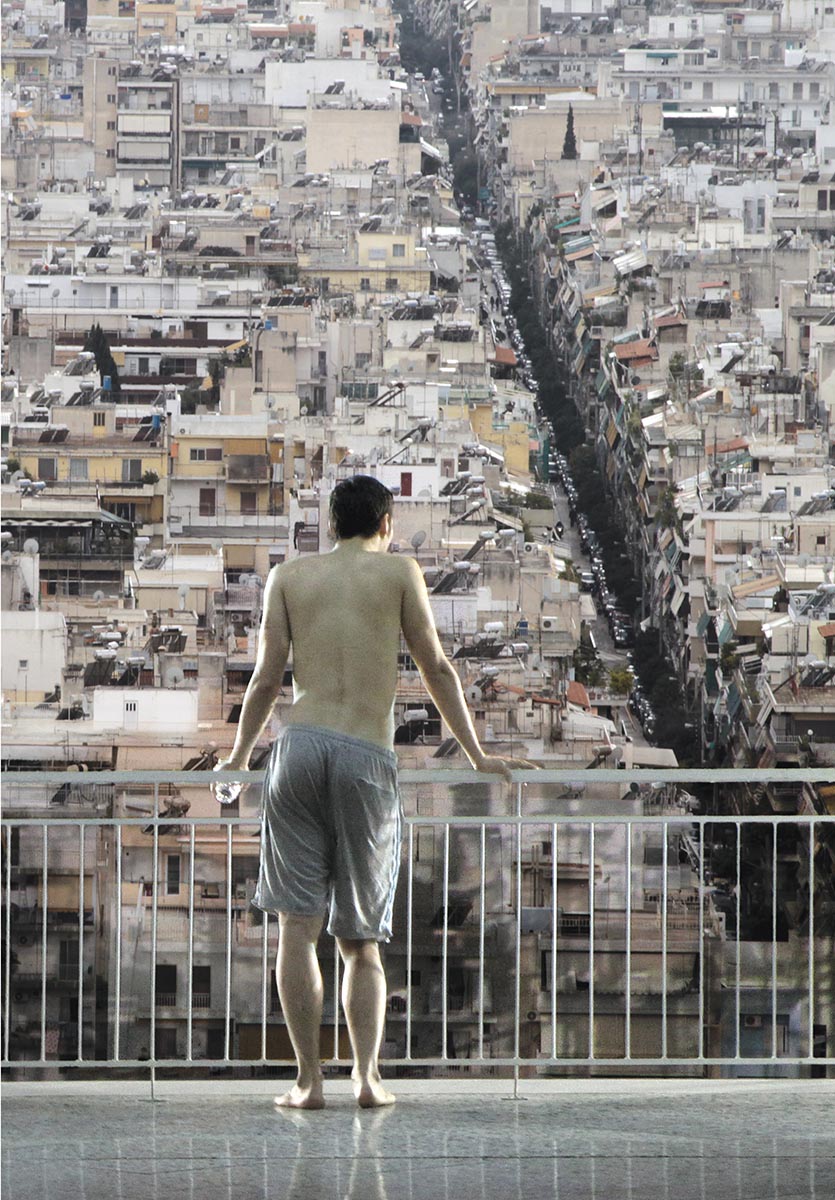

Someone enters. They take their coat off and then their shoes. They go to the bathroom; they pause, they shower, they dry off and then go to the kitchen. They eat something, they drink water. They go out onto the balcony. They take in the view. They return inside. They lie down on the bed. They pull the blanket around themself. They sink.

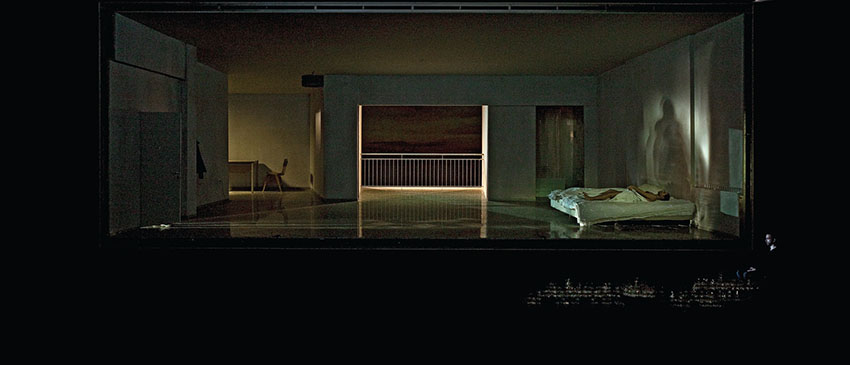

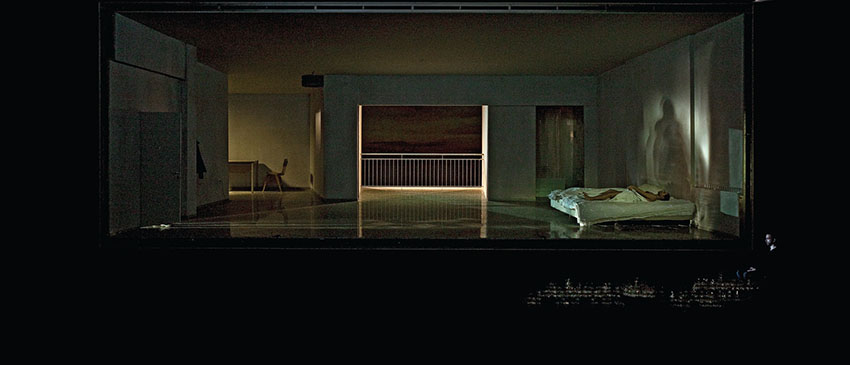

This deceptively simple set of motions forms the choreographic backbone to the unclassifiable epic INSIDE by Greek artist, filmmaker and choreographer Dimitris Papaioannou. Initially staged as a six-hour-long durational theatrical installation in Athens during the spring of 2011, INSIDE weaves an intricate web of repetitions that saw thirty dancers perform the same set of mundane homecoming chores and rituals one after another in a cavernous set that mimics a nondescript apartment that could be found almost anywhere and everywhere in Greece. Falling in and out of synchronicity, the sequences of what one may consider an ultimate expression of domesticity and ennui reveal an innate poetry to how people relate to their most intimate spaces in solitude.

Now presented as a monumental video installation in Freespace, the transformative spatiality of INSIDE offers a private, sometimes almost intrusively so, gaze into the universal condition of being a person in the present day and what is left once the veneer of the social self is left on a coat rack. In some ways a work of autofiction – Papaioannou confesses with an impish glint in his eyes during the interview for this text that this work partly drew on his desire to be alone, his little idiosyncrasies when alone at home and his voyeuristic impulses – INSIDE collapses the boundaries of individual memories within a single room and, in doing so, creates a particular aggregate of embodied, instinctive histories that both provoke different perceptions of how time passes and consolidate a particular rhythm of neurosis and identification endemic to this urban century. As Papaioannou notes, INSIDE returns to the audience what the audience gives to it – time and time’s capacity as a substrate for imagination.

The multi-hyphenate Papaioannou trained as a painter in the classical tradition in his youth before moving on to contemporary modes of graphic arts and, eventually, performance, within which he dwells with a preternatural self-assurance. He shared that, in his practice, movement and stillness carry the same meaning as the proximity of objects and other elements in a visual composition; and thus when he makes theatre and performance, it is also through the eye of a painter. His choreographic principle is rigorous to the image and its transformations, between motion and fixity, between appearance and disappearance, that speak to how time and space necessarily configure their own passages and their impacts on bodies, things and environments.

This rigour is likewise mirrored in the making of INSIDE, which, despite its almost casual appearances, is precisely timed to a choreographic score of six hours for every entrance and action of every performer through a blinking light system backstage. Meticulously devised on his computer, Papaioannou’s manipulation and multiplication of the gestures of one performer to a final ensemble of over thirty bodies is undergirded by an almost digital logic in how he envisions the works of layering and superimposition. Though seemingly unorthodox, the method to the madness speaks to the totality of how Papaioannou approaches his craft in what he terms as the “calculation of the emotion of light”, a poesis that goes beyond a reductive definition of the choreographer as a proponent of specific gestures to encompass the artist as the author of how narrative, space and shadow can constitute a new vocabulary and experience of something close to the sublime.

Not forgetting the specific textures of the performers, Papaioannou also ventures that as the cast are all from the Mediterranean, the natural exuberance of their expressions, both performatively and individually, required a strict regime of training and practice to be modulated and essentially deprogrammed in the performance of INSIDE. Through this necessary process of disciplining, the cast also acquired an almost spiritual sense of suffering even as granular details of personal subjectivities are slowly and subtly shed. In this way, the uniform choreography highlights the tensions between the voyeuristic gaze and the inscrutability of interior emotions even when subject to close observations. One aspect that did draw upon the personalities of the cast is the large-format video montage that constitutes the main view from the balcony in the set. Produced with media contributions from the performers, each segment relates to a performer in specific but unarticulated ways that contribute to the mosaic, polyphonous consciousness that Papaioannou tries to engineer.

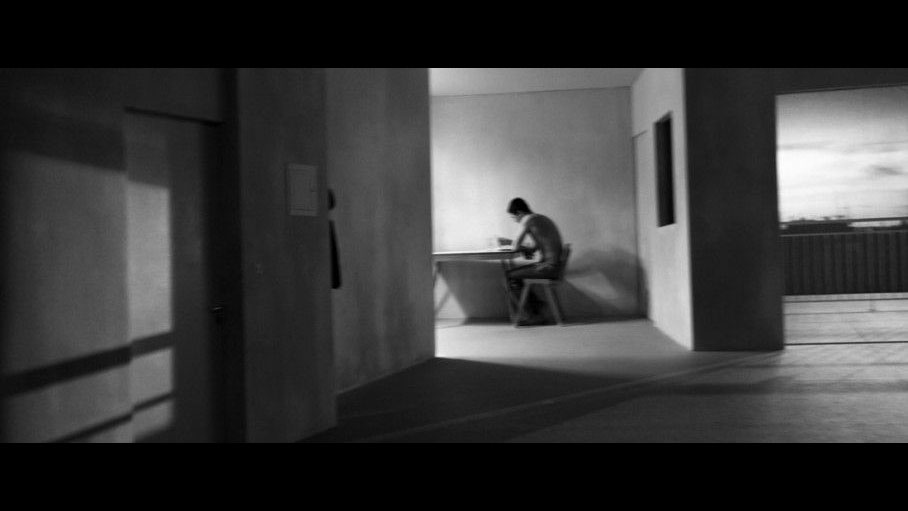

Made in tandem with the original staging of INSIDE, the documentary work of BACKSIDE inverts the voyeur to make visible and deconstruct the obscured processes of self-fashioning and presentation that accompany formal theatrical productions. Keyed to the aesthetic sensibilities of filmmakers such as Greek-American director John Cassavetes, Papaioannou makes full use of a new representational vocabulary inherent to cinema with his usage of jagged cinema verite shots and ragged editing style in BACKSIDE that runs in contrast to the austere minimalism of INSIDE, for which he cites the works of English painter David Hockney and the canonical Edward Hopper as some inspiration that he paid homage to. Papaioannou reveals a conscientious reflexivity in the ways that he had designed BACKSIDE to exist as a contrapuntal to INSIDE: he confesses that he does not like secrets in art, preferring to understand and be shown the process of transformation from canvas to painting, from faces and bodies to choreography.

Asserting that the central contract between the artist and the audience is to meet on the common grounds for imagination, Papaioannou’s curiosity for this relationship drives the making of BACKSIDE as an additional layer of both visibility and obfuscation in the illusions of continuity and placidity that are engineered in INSIDE. He notes that play and make-belief occupy a central role in human development, most evident in how children play and make sense of the world around them, investing the labour of imagination in creating parallel instances of truth that are generative and generous. By revealing the craft of theatre, Papaioannou thus imbues the discovery of secrets and operational techniques with a kind of enchantment that precipitates a richer reading of the overall project and, in doing so, allows for un-self-conscious moments of introspection.

In the Hong Kong staging of INSIDE, Papaioannou asserts that the filmic and installation qualities of the work maintain an agency in how space can be created and occupied freely for the audience to meditate, be a voyeur and imagine – the crucial component here is in the possibility of an internal journey that uses INSIDE as a point of departure or consideration. Indeed, the construction of the voyeur as a perspective of not perversion but an almost naive curiosity is central to how INSIDE functions. Commenting that as a youth, he too was fascinated by the fragmentary exposures to the daily lives and intimacies of the people he encountered, Papaioannou denotes the spectator of interiority as a position through which the gaze becomes a trajectory towards a kind of truth and honesty. An additional element of the Hong Kong staging that Papaioannou is particularly excited by also reflects and refracts on the materiality and spatiality of how INSIDE has expanded through the gaps between the mediated surface of the screen and its physical incarnations, much like a quiet temple.

Pointing out that in live stagings of INSIDE as a theatrical installation a recurring motif is the steady piling of water glasses from each character who leaves and places a glass somewhere in the room, Papaioannou calls attention to how the gesture of placement pushes an earlier glass further outwards from the stage until the point where a glass will always drop off the stage and the works of one performer, who will steadily place glasses on the theatre floor until a veritable glass city forms under the stage. Gradually coalescing into a city, the accumulation of glasses into little crystalline towers mirrors the accumulation and documentation of bodies, memories and souls within the urban landscape itself as each incarnation of each performer leaves behind a material trace of their presence that overlaps and overlays. Given the conditions of how INSIDE will be presented in Freespace, the glasses will be recreated as an installation component that accompanies the main screen and provides a different dimension to the transmission of affect and stories across time and geography.

The question of movement and transmission is also something Papaioannou is grappling with in his own practice. Sensing a shift in his relationship to creation and production, he has also begun working on re-editing and recontextualising the vast trove of archival materials gathered over the course of his decades-long career into new spatial configurations and atmospheres that can have their own artistic autonomy, liberated from the place and theatres of their initial staging. Ruminating over the meaning of theatre in the present day, Papaioannou shares that it functions as a sort of social psychotherapy where community may collectively reflect upon things and issues too painful to encounter outside the confines of fiction and narratives, much like how the ancient Greek theatrical traditions of the tragedy and comedy served to extirpate and regulate social emotions that help to eliminate hubris. “It is one of the last things that we gather to experience together,” said Papaioannou. “It's sports, music and theatre.”

Someone enters.

Stage installation presented at the Pallas Theatre in Athens, Greece, in April and May 2011, across 20 performances.

Photo: Julian Mommert

Concept and Director

Dimitris Papaioannou, born in 1964, is an internationally acclaimed Greek director, choreographer and visual artist. The youngest artist to direct an Olympic Games opening ceremony (Athens 2004), Papaioannou was the first artist invited to create a work for Tanztheater Wuppertal after Pina Bausch’s death (Since She, 2018) and the first Greek artist to receive a Europe Theatre Prize (2017). His extensive body of work includes The Great Tamer (2017) and Traverse Orientation (2021), which have been presented at major venues worldwide and toured over 30 countries and 50 cities. His recent work, INK (2020), featured the artist himself on stage and concluded its tour in the spring of 2024.

For more programmes, please visit:

Overview page