*with post-performance meet-the artists session

Part of the Thai and English dialogues has Cantonese interpretation.

Approximately 65 minutes without intermission.

The audience is invited to join a 15-minute pre-show interactive session starting at 7:45pm on 29 and 30 November and 2:45pm on 1 December.

Before the performance begins, please switch all devices to silent mode. Non-flash photography and short videos (maximum 30 seconds) are only allowed during the interactive sessions.

สวสั ดคี ะ่ ทกุ ทา่ น ยนิ ดตี อ้นรับสศู่ าลดจิติ อล (Hello everyone, welcome to the digital shrine!)

I’m very happy to be part of Freespace Dance this year and have the opportunity to connect with all of you here at WestK, Hong Kong.

In this reimagined space, we are creating our own system of personal beliefs and spiritual connections within a digital shrine. As we explore the boundaries of belief, we are also discovering what it means to hold on to hope in a digitised world as digital nomads. Here, in Mali Bucha: Dance Offering, dance becomes a code that shapes the dynamics of belief systems. Visuals, sound and dance find a balance together between physical and digital spaces. Through this work, I am contemporising a tradition, bridging the gap between the spiritual and virtual worlds. I’m excited to invite you on this journey at Freespace as we explore how technology can create new spaces for cultural expression and spiritual connection.

Title of Song: เพลงเชื้อ (loosely translated as Song of Believing)

Phonetic Alphabet: Phelng cheụ̄̂x (English pronunciation: Pleng Sher)

Rough translation of the lyrics for the occasion of Mali Bucha: Dance Offering:

I pray to the powerful and sacred.

Humans rely on you for blessings to make their wishes come true.

I am in front of the Digital Shrine.

I work for those who return dance offerings to the Digital Shrine as appreciation for the blessings.

Text: Lim How Ngean

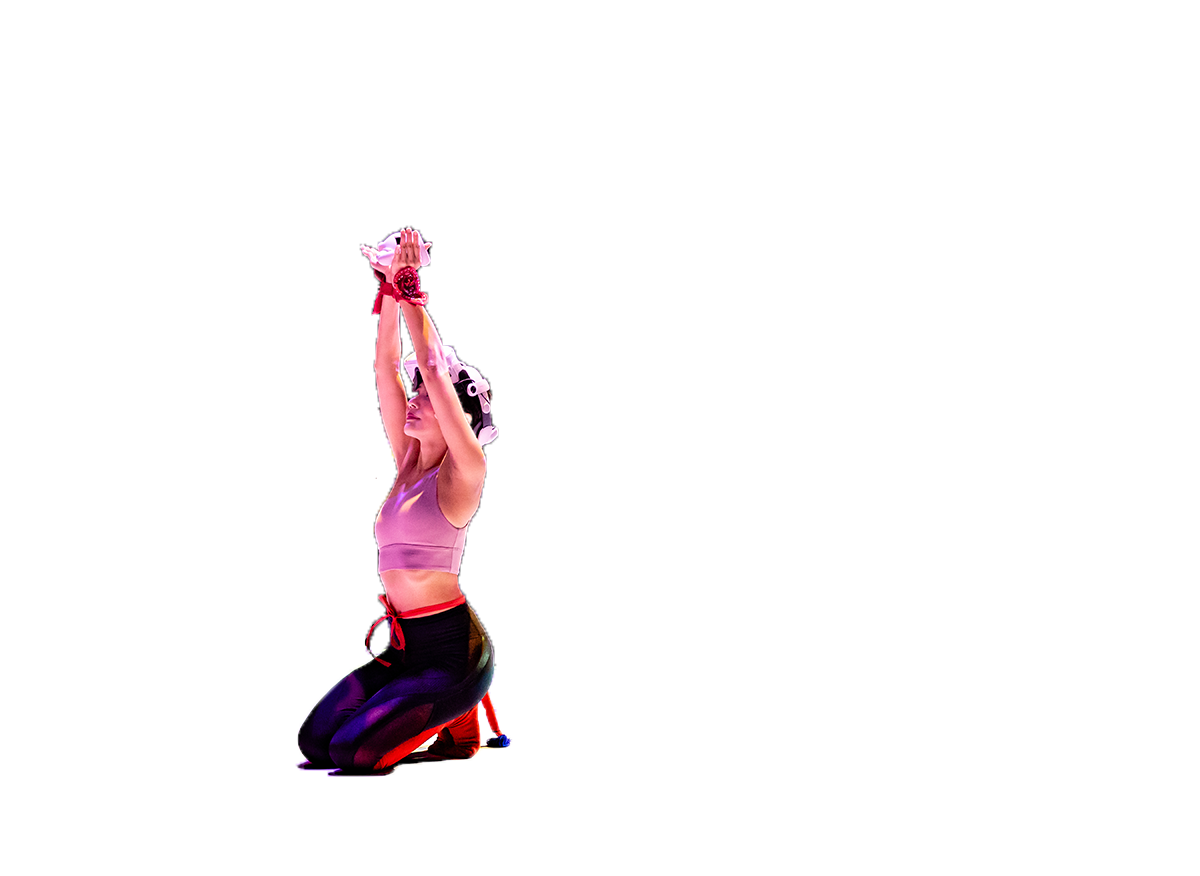

Contemporary Thai dance artist Kornkarn Rungsawang is sending out more than good vibrations in her latest performance Mali Bucha: Dance Offering.

Time and space took on a multitude of new meanings during the pandemic. Not so long ago, we faced the then dreadful present and uncertain future marked by the stretching of personal spaces through social distancing, the slowing of time and the contraction of private as well as public areas with prolonged lockdowns. There was even a suspension of time in confrontation with mortality and more harrowing existential questioning of losing track of time.

No stranger to expanded notions of time and space, dance artist Kornkarn Rungsawang also began to experiment with space-time permutations in her aesthetic practice. In the swirl of lockdowns, shut-outs and left-behinds in her Bangkok home in 2020, Kornkarn thought long and hard of the loss of social, cultural and spiritual connections during the pandemic. She recalls, “I didn’t know what the future was going to be, how much we might lose and not knowing how long the lockdown would continue. People were not allowed to go to the temple to pray to Buddha. And then we began to connect with people online, talking to someone, finding out what’s going on around the world.”

Digital technology at the height of the pandemic rose to the fore in nurturing human relationships through the myriads of electronic social and meeting platforms. Drawing from her folk and traditional background of Thai dance, the contemporary dancer then studied these digital platforms and proposed an idea to rekindle spiritual connections for her community locked-down in Bangkok: “I wanted to find a way to connect with other people online and find a way to pray or make wishes for the future in a digital world.”

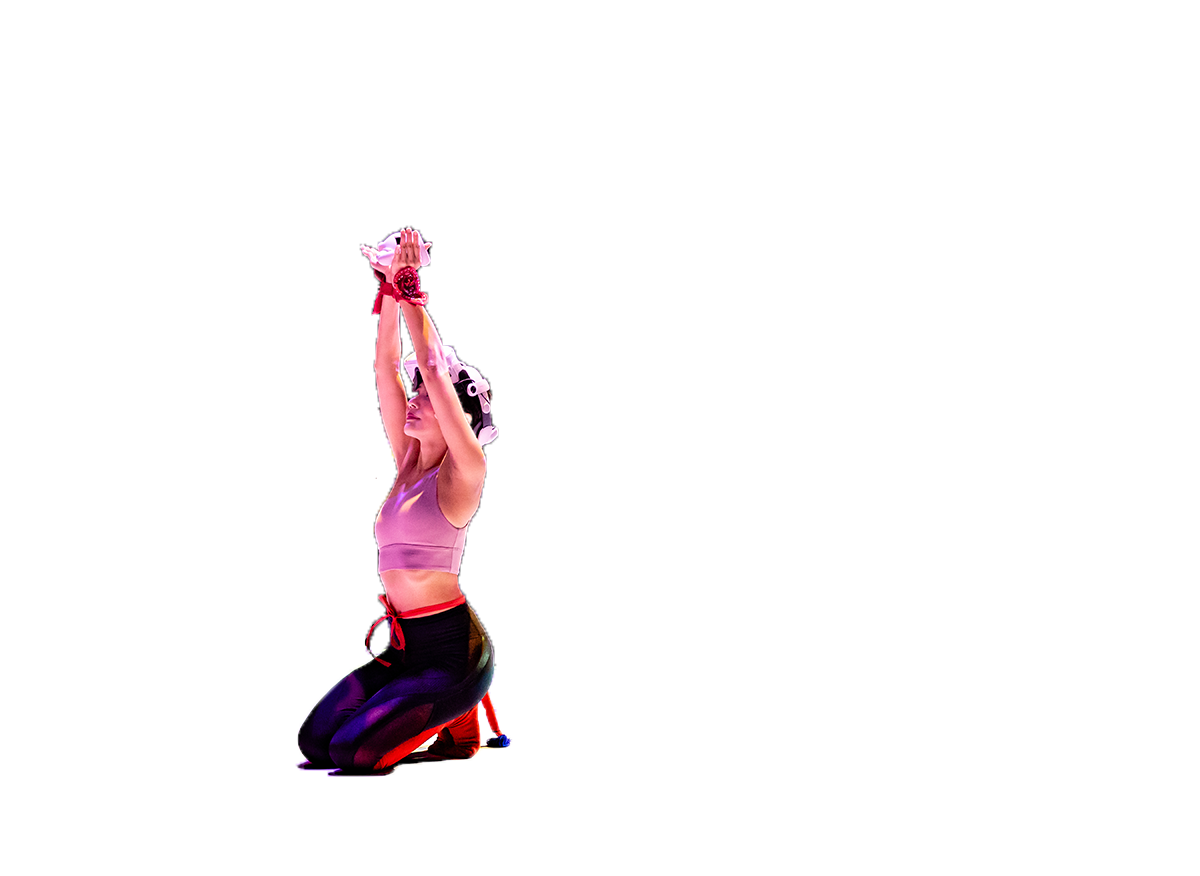

She became inspired by a rich and complex Thai belief in which offerings are made to the gods or spiritual or heavenly beings to pray or implore for the worshipper’s wishes to come true. Other than material goods such as food, money and flowers, the Thai people also traditionally engage dancers to send their prayers or wishes to the heavens. Ram Kea Bon literally means dance offering in the Thai language. It connects to Thai people’s beliefs in using dance as a way to negotiate with higher beings to make wishes or prayers come true,” she explains further. Kornkarn would then slowly conceptualise a dance project that would eventually take the form of Mali Bucha: Dance Offering, her debut solo performance.

“As a traditional Thai dancer, I am a medium – an interface – in the ritual of Ram Kea Bon to help communicate between devotees or worshippers and higher beings. My dance is offered to the higher beings as prayers and wishes. In Mali Bucha, my role as interface includes that of the dancer, but there are also technological means as I guide devotees – or anyone who wants to make wishes – into a digital world. I use different tools as interfaces to connect physical, spiritual and digital worlds.”

Mali Bucha presents a hybrid understanding of belief and spirituality by moving and transporting audience members between the physical world and the digital realm through a virtual shrine. There is enough scientific and religious research, debates and studies at present that link the theory of spiritual ether to that of the digital realm. Kornkarn proposed a somewhat more practical yet creative and aesthetic approach in her performance: “The audience can access a digital shrine with me while they wear a virtual reality (VR) headset. We then move together to ask for our wishes to come true.” In addition to VR technology, Mali Bucha boasts of another vital component in the form of augmented reality (AR) where audience members can participate in selecting types of wishes or prayers – to ask for health, wealth or love – in the form of different icons while they are transported in a digital shrine in the form of different avatars. While Kornkarn composes her own body in dance, she also choreographs how audience members can participate in the performance. “I am interested in marrying old and new ways of dance, tradition and ritual with AR and VR technologies to explore belief and ritual in the digital age.”

Kornkarn is quick to add that this is not a performance that focuses on a specific religion or distinctive religious rituals. She emphasises that Mali Bucha brings the message of hope rather than religiosity. “I had a question in this work, that is, what it means to hold on to hope in the digital world as a digital nomad. We don’t really know where our hopes [or wishes or prayers] go, but we still possess hope. We hold on to our hopes, and we share our hopes with one another. Through hope, we believe in what is good, and we share this belief as a way of caring for each other together,” she stresses.

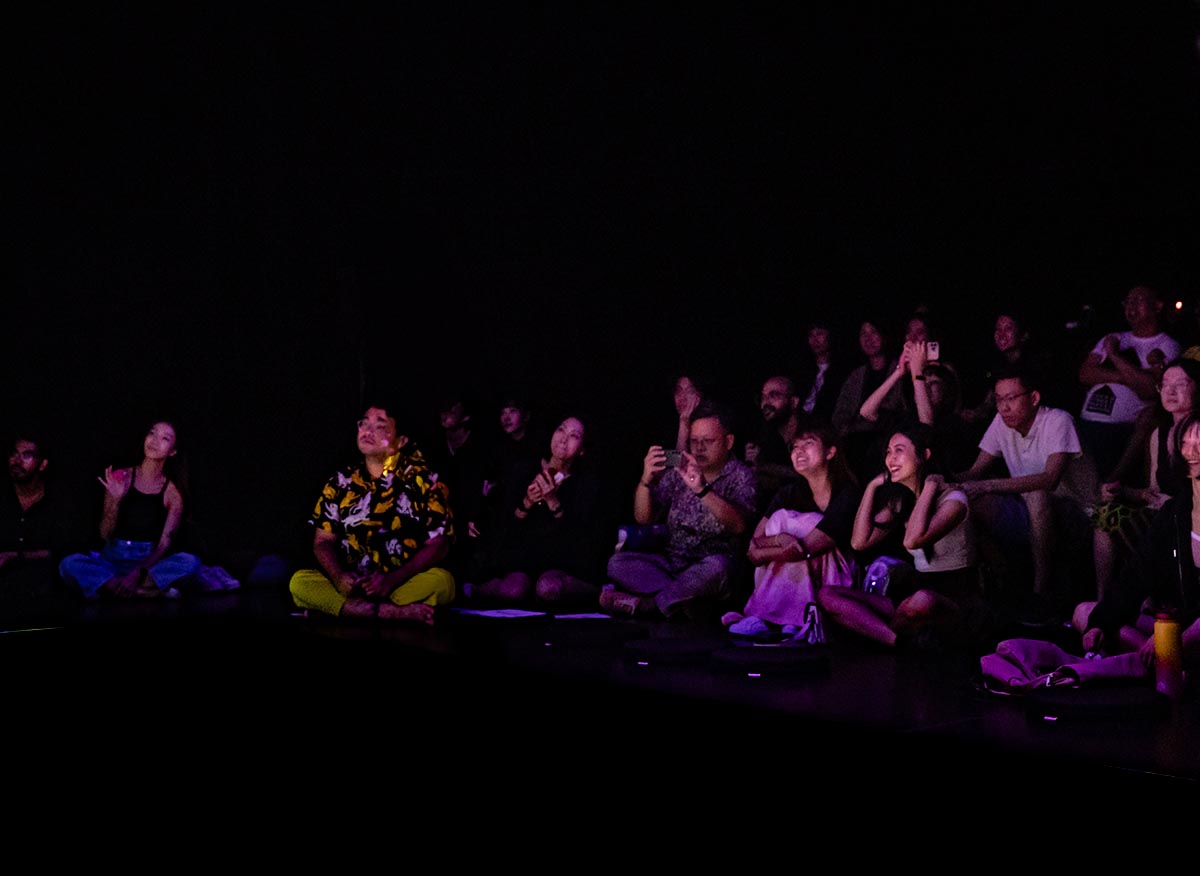

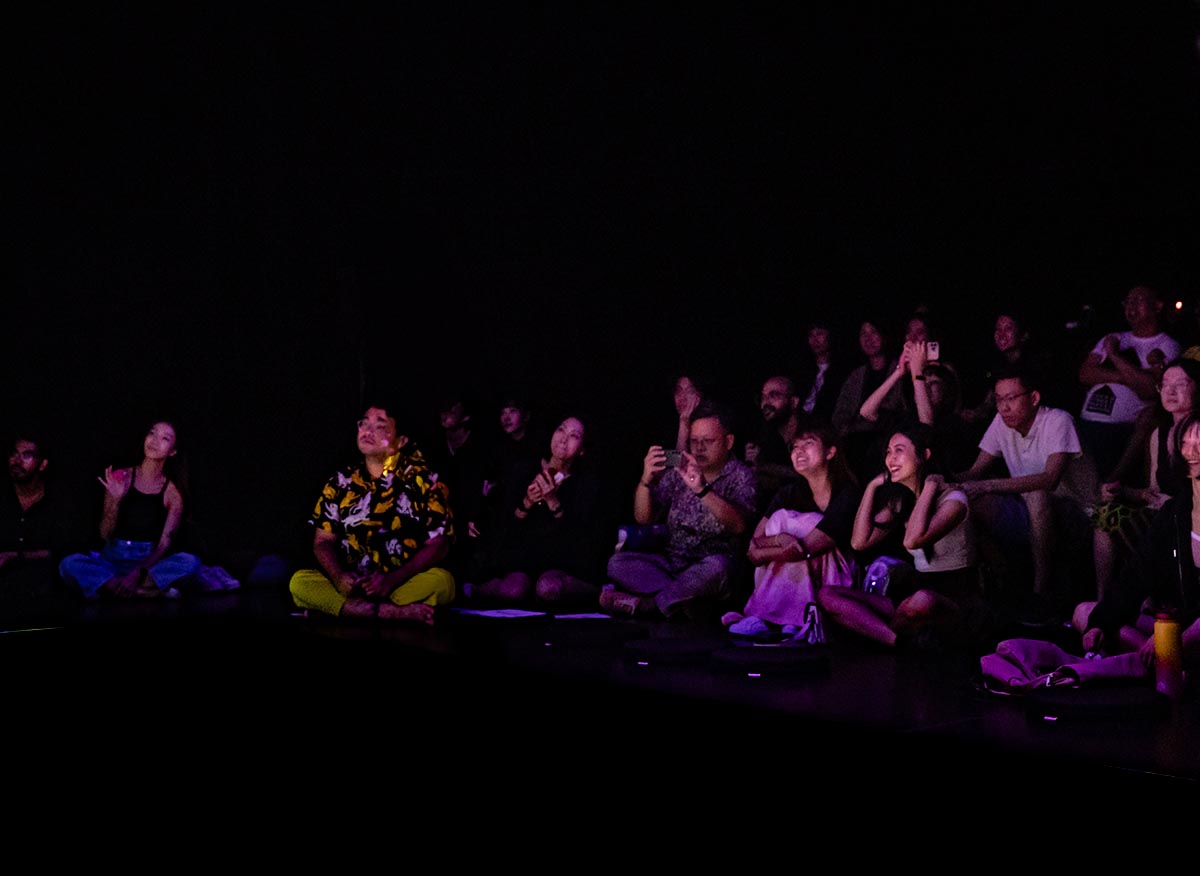

There have been several versions of Mali Bucha, from various workshop editions during the pandemic to a premiere in Singapore in 2023, after the world reopened. Presently, Kornkarn is happy to report that the version to be staged in Freespace Dance 2024 at the WestK Performing Arts Presents: Season 24/25 strikes a balance of online (VR and AR) aesthetic elements intermingling with offline choreographies (physical activities on stage). She elaborates how different spaces and times exist in Mali Bucha: there is the here and now of the present stage where Kornkarn engages with audience members. Then there is the imaginary time and space carved out by individual audience members with their wishes and hopes, and finally, there is the digital shrine where yet another space and time exist, to which Kornkarn helps audience members send their wishes and hopes. “The audience completes this work. Together with the audience, we create a world where we send our hopes to, which is the digital shrine.”

As the piece evolved and developed, Kornkarn discovered that the performance changed in very nuanced ways. For her, the subtle changes are prompted by how audience members participate and react in the performance. “We create a code of gestures; the audience contributes to writing the code for the digital shrine. These are gestures from the audience members who want to send their hopes and wishes to the digital shrine. The code of gestures in turn shapes the belief dynamics and system of the digital shrine. By doing so, the digital shrine becomes powerful and real based on what the audience members physically put into it.”

The cultural significance of Mali Bucha cannot be overstated, as audience members from different cultural backgrounds imbue the work in different ways. Kornkarn gave the example of Mali Bucha in the Toyooka Festival, Kinosaki, in western Japan last September. “Many of the locals there did not speak English, so I had to try a different way of communicating with them. I learned that I could use hand gestures to communicate with them. I would use different gestures to symbolise health, love or wealth so that the local audience would know how to follow us on the journey to send wishes in the digital shrine.” According to Kornkarn, the local Toyooka audience members were also older members of the community, but they were open-minded enough to try different things. “Of course, I had learnt a few Japanese phrases to help me get the message across, but it was mostly through gestural work that we began to come together in the digital shrine,” she adds. Therefore, it would be interesting to see how Kornkarn interacts with the Hong Kong audience – she promises to learn some Cantonese to connect on a very local level at Freespace Dance 2024!

There is obviously a large component of the performance that is driven by technical literacy as Kornkarn navigates with the audience through the different media of VR and AR. The collaborative work with other media artists makes Mali Bucha ever more challenging – and more engaging – as the performance is a symbiosis of bodily technique and contemporary choreography (conceived and performed by Kornkarn), video and digital design (with a team comprising Matsumi Takuya, Hara Junnosuke and Suzuki Kazue). To tie this up would be the requisite lighting design (Miura Asako) and sound/music design (Zai Tang) to produce a cohesive performance project that goes beyond technical virtuosity and precision. Mali Bucha is a human story grounded in heart, intelligence and humour. Kornkarn is passionate about finding her connection between traditional and folk training with contemporary artistic sensibilities. She says, “The main question for me as a dancer for now is to explore and work on how technology works with tradition and how the traditional can move into the future. I try to honour my traditional dance principles by moving forward in my contemporary work.”

She is aware of her privilege as a contemporary artist in her homeland of Thailand, where support of all kinds is scarce. Funding in contemporary performing arts in Thailand remains a challenge for many artists. “It is difficult to survive as a contemporary dancer in my country, and so I know I am lucky to be supported by arts organisations in other countries such as Singapore and Japan.” Mali Bucha started life as a research residency hosted by Singapore’s Dance Nucleus and was eventually developed in another residency in Kinosaki International Arts Center, Japan. It finally premiered in Singapore’s Esplanade Theatres on the Bay in 2022.

More than that, contemporising traditional art forms is generally frowned upon in the Thai traditional performing arts community. It is considered disrespectful of what is considered essentially authentic Thai art forms. “I have problems applying for funding in my own country when I touch on changing aspects of my traditional training. I think the younger generation is more open-minded, but I have not performed Mali Bucha in my own country yet, so I really don’t know,” she quips.

Yet Kornkarn lives to perform: “I feel alive when I work in the theatre. It wakes me up! The theatre is home where I can connect and communicate with my audience. It is also a place of hope for me. The theatre also gives me a space to challenge my thinking and to express what I think and feel through my dance.”

Lim How Ngean is a dramaturg who focuses on dance and contemporary performance. He has worked with notable choreographers from the Southeast Asian region, including Eko Supriyanto and Pichet Klunchun. He also founded the Asian Dramaturgs’ Network (ADN) that is based in Centre 42, Singapore.

Photo: Nattapol Meechart

Concept, Choreography and Dance

Born in Bangkok in 1988, Kornkarn Rungsawang represents a new generation of dance artists whose aim is to bridge the traditional and contemporary. Trained in diverse Thai traditions, from royal court to popular folk forms, she applies her knowledge of traditional kinaesthetic systems to the contemporary body and urban rhythms to formulate new dance expressions that reflect the current social, cultural and political environment. Since 2010, Rungsawang has been a full-time artist with the Pichet Klunchun Dance Company. Since 2021, she has been developing her own performances with the support of a growing international network of presenters in Asia and Europe. After developing her solo work in Asian and European dance institutions, she premiered Mali Bucha: Dance Offering in October 2023 at Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay in Singapore.

Mali Bucha: Dance Offering is a commission of Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay (Singapore), in co-production with Kinosaki International Arts Center (Toyooka, Japan).

The project has benefitted from residency and research support from Chang Theatre and Pichet Klunchun Dance Company (Bangkok, Thailand), Dance Nucleus (Singapore), Tanzkongress (Mainz, Germany), Indonesian Dance Festival (Jakarta, Indonesia), Tjimur Arts Festival (Pingtung County, Taiwan) and Kinosaki International Arts Center (Toyooka, Japan).

For more programmes, please visit:

Overview page